I have several ideas going on that I want to make posts on – but for them to make sense I think I first have to go through some of the ideas they build on, so I can link back to this whenever needed, instead of having to repeat the same arguments over and over. Also, this post is also an excuse to be able to talk a bit about some things I have been diving into lately.

In this post I will be focusing on philosophical applications of dynamical systems theory (you could say that I am reinventing complexity theory, I do not think so, since what I am trying to do is very much different, although I share the same inspiration). I have no claim of actually doing science, or even engaging with science on its own terms (in this post atleast).

I remember seeing a discussion on twitter wherein both parts were criticizing the field of complexity theory for misusing terms from the field by reading too much into them, and being far too disciplinary. I agree with these criticisms, and I want to avoid doing the same. However:

What I am interested in is philosophy, and using science as an inspiration for it. If it is not fully accurate of what ”science intended”, so be it! I am not interested in trying to appeal to the authority of science for it to judge my arguments to be truthful. When I speak of scientific concepts, I am doing it from a philosophical perspective, not a scientific one. I do, still, want to be able to convey them in a way that lives up to the phenomena they are trying to explain. I hope I do not completely butcher these ideas.

Crash Course in Dynamical Systems Theory

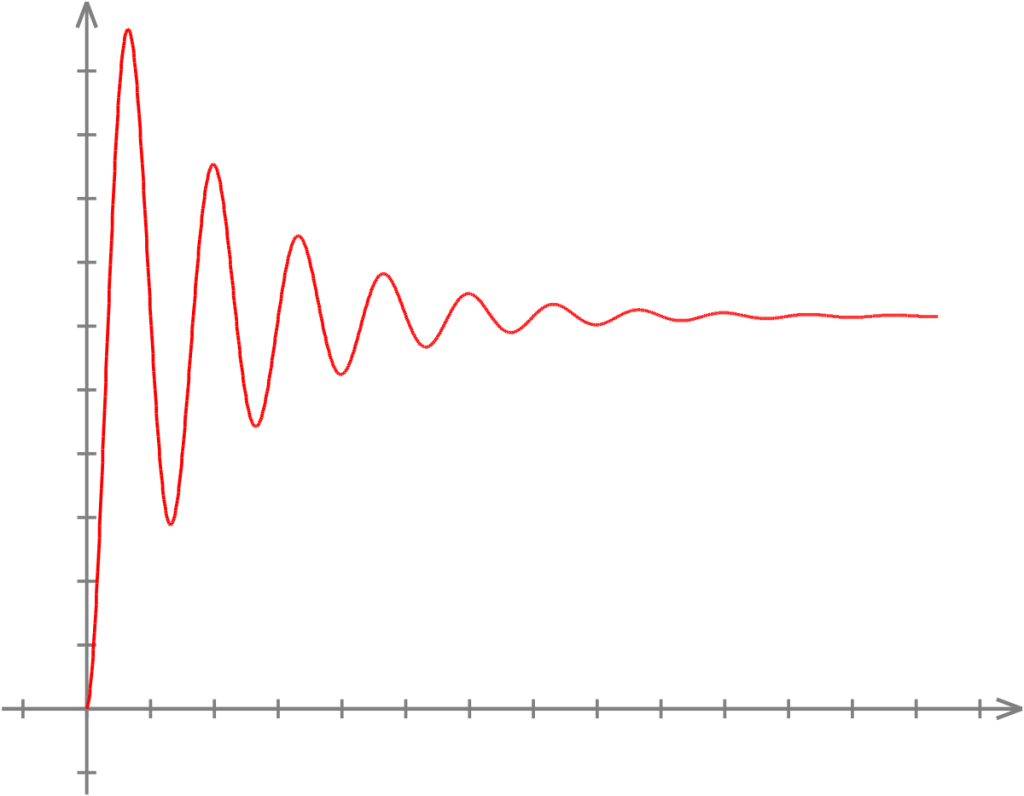

In a population diagram you get a curve of how a population evolves over a period of generations. They will usually take the form of overshooting, then coming up short – and so on – but stabilizing once you give it a while. These behaviors arise easily from very simple processes – growth rate versus limiting factors (of the environment). So, if the vertical axis is the amount of individuals in the population, and the horizontal axis is time:

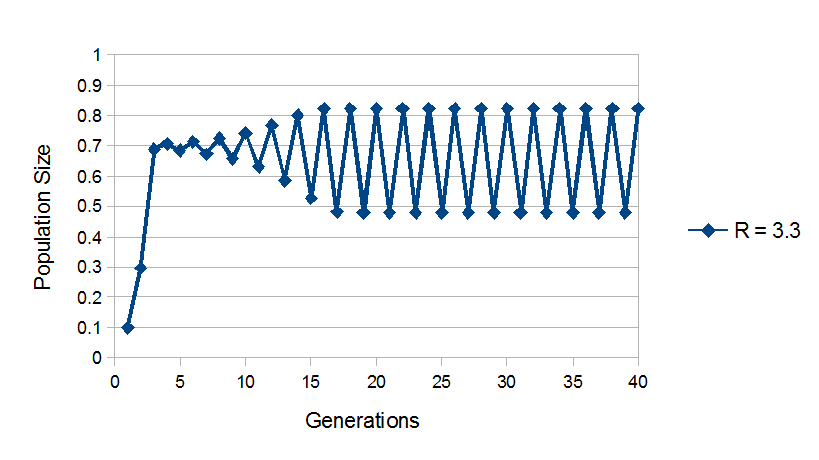

However, if the growth rate is high enough relative to limiting factors, it will not stabilize into a single line, but instead into an oscillation between two points:

And if the growth rate is even higher – into a four point oscillation:

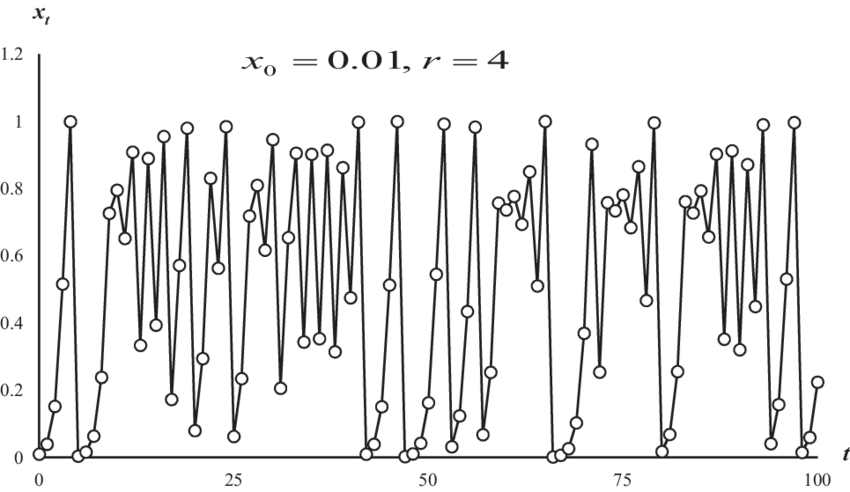

If we keep increasing the growth rate for a while, it starts looking like this:

This last one is said to be chaotic. So what is going on here? There seems to be some sort of pattern going on, that then breaks off into something that seems far less patterned.

So, let us make a diagram of these diagrams – trying to track how the amount of oscillation points collerates with the growth rate:

This is what is called a bifurcation diagram. Up until a growth rate at around three, it stabilizes into a line – while after it stabilizes into an oscillation between two points. Then from two into four, four into eight – and this keeps on happening faster and faster. When that pattern becomes small enough that we cannot discern it, we have reached what we call chaos. That is – it is not that there is not any sort of pattern, just that it oscillates between so many points that it appears, for us, chaotic.

The thickness around the first bifurcation point (where one line turns into two) is explained by the fact that it takes an incredibly long time for the function to stabilize into the pattern it is tending towards. Since you usually only let the function iterate a few hundred times, it is still uncertain if it is one or two points. However, if you’d let it iterate for a longer, it would be more sharp and accurate – but this requires far more computing power, and sometimes makes certain patterns less visible.

I understand the bifurcation point as being the place at which the time to stabilization becomes infinite. That is, where we classify it as two points instead of one – and so on. It is like a line that shoots of into infinity and then folds over itself to do so again, and again.

(The idea of a bifurcation only being the time to stabilization becoming infinite, is one I will try and use in the development of a philosophical concept of space-time, and maybe consciousness aswell, in a future blog post)

An overeager hegelian or marxist would maybe call this analysis of bifurcations a perfect example of quantity into quality. I do not necessarily disagree, but I do not think it can be used as a proof of the dialectic occuring in nature. Rather that concepts, like the dialectic, is inspired by – and tries to explain – patterns that occur everywhere. Many different philosophies try to explain the same behaviors – to then see those behaviors as a ”proof” of philosophies is nothing but a confusion.

A central part many find interesting with the bifurcation diagram above is how simple functions lead to such complicated patterns. These sort of results is what leads people to wanting to apply the idea of ”emergence” to everything that moves (or doesn’t). For example, the unexplainable aspects of consciousness are sometimes called emergent from a simple logic of neurons – or the whole of society is emergent from the individuals it consists of. I think this is an easy way to admit the existence of complex high level entitites, while still fundamentally sticking with atomism (the idea that the true nature of things is found in their most fundamental components).

However, unfortunately, emergence does not really explain anything in itself, unless you have a good argument or proof of how this emergence comes about. Nothing is explained by claiming that consciousness is ”emergent” unless you say how it is so. Otherwise it just becomes nothing more than an excuse to stick to a dogma of atomism in the face of complex entities seemingly irreducible to their components.

I do not claim to want to stick with atomism, therefore I feel excused from trying to explain this through the lens of emergence. But that does not mean that I will not try to understand it by other means.

So, can I explain how the patterns in chaos emerges? Without simplifying, what is going on in chaos?

I do not know! Which makes me wish I was studying this instead of doing philosophy. In the lack of certain knowledge, let’s plunge further into chaos and make it weirder and see what will come out with us on the other side.

There was this amazing thread I saw on twitter the other week that is quite detailed on this sort of perspective. The account, Build Soil, is really great and I recommend you check it out:

It seems that rotating the bifurcation diagram gets us the mandelbrot set.

What is the mandelbrot set?

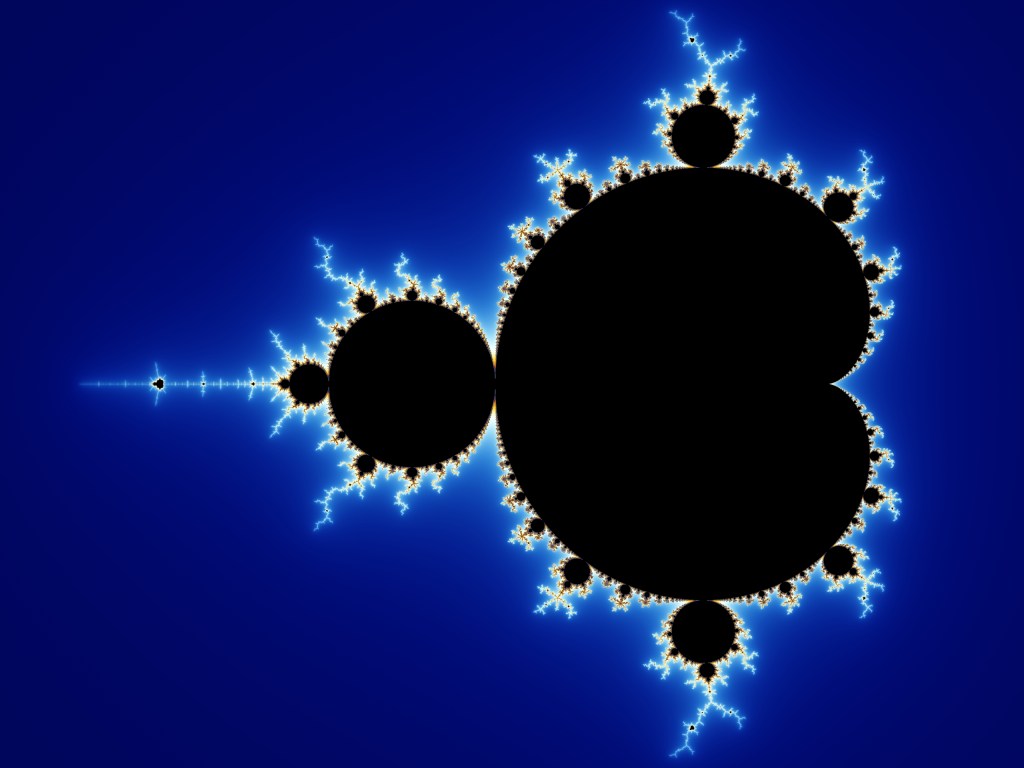

The mandelbrot set is defined by iterating a function a certain amount of times. If it becomes clear that the function tends towards infinity, it is not a part of the set. If it instead stabilizes – then it is a part of the set. Doing this over a plane of real numbers (horizontal) and the irrational numbers (vertical), you get this image:

It is very clearly a fractal. Actually, the bifurcation diagram is also a fractal, but I think it is less obviously so, for people without much knowledge of what constitutes one.

There has been a category of videos on youtube since forever really, of ”infinite fractal zooms” and so on. Here is an example:

A Complicated Journey – Mandelbrot Fractal Zoom

I like this one because it doesn’t just zoom in at a ridiculous speed. Instead it takes it slower, and as a result, the video becomes incredibly long. It lets you see details before they are out of view. I think it gives an even grander sense of scale – I cannot but try, although impossible, to imagine how large the entire object would be, at the level of zoom you reach towards the end of the video.

These videos are of course not really anything new, but I think it is good to be reminded of, as I discussed earlier on the topic of emergence, how unimaginably complex these structures appear, following from very simple rules. I don’t think that this has to mean that the world is fundamentally simple, following a single principle, or anything like that – rather that the distinction between the simple and the complicated often does not exist.

So, how does the connection between the mandelbrot set and the bifurcation diagram make sense?

While they are both obviously related to some sort of oscillating patterns, considering their definitions, I cannot fully account for how. I do, however, have a baseless speculation:

Each bifurcation point is also where the mandelbrot set becomes compressed. This could be because it takes longer and longer for the function of the bifurcation diagram to stabilize, which means that it becomes closer and closer to instead shoot off into infinity. At the bifurcation point, it is split in two, and then the mandelbrot set can expand again. This explains why the mandelbrot set becomes smaller and smaller, except for those small Islands: it is because of the bifurcation diagram getting closer to chaos. This can be seen in videos illustrating the same points in a bifurcation diagram and the mandelbrot set.

To return to the beginning of this section – population dynamics – I think Build Soil describes it it beautifully:

Further Thoughts

The mandelbrot set, and the bifurcation diagram, is fundamentally about the sustainability of change. How intense can a given process(/function) be, given the limiting factors of its environment, before it becomes unsustainable? These are questions that are of obvious political consequence. Not just with climate change, but also for antagonists against such entities as the state, capitalism, or civilization. Or, as Build Soil said above – about the fundamental conditions, or processes, of life. Even more, it shows how one force, for example ”growth”, does not always lead to a larger population – even though that seems to be a sort of telos of that force. There is no clear cut path of doing x and then the ideal of x occuring as a result.

What is chaos then? It is important to not import other ideas of what chaos means when talking about this – chaos does not mean collapse. It just means patterns that are too complex for us to grasp. Think of white noise – the sound of every frequency playing at the same volume. It is perceived as purely chaotic for us, we cannot discern any tones in it at all. At the same time, white noise contains every possible melody, every possible sound, and every possible voice in it. All of the world is spoken simultanously in it, which makes it impossible to discern any specifics. We need to draw out a pattern to be able to discern anything – we need to put in limits. A chaotic system does not appear to be a system to us – it is a call for us to redefine what constitutes the system, to make something a bit more predictable – something that more approximates the less bifurcated parts of the diagram.

As I mentioned before, however, chaotic does not mean unpatterned – only that it appears unpatterned for us. This means that the amount of bifurcations you can reach before the system becomes seemingly unpatterned is purely limited by our ability to make sense of it. To speculate further on this, it seems to me that computation becomes important: allowing us to find patterns much further into ”chaos” than by just using ourselves. In this way, computation/technology complicates our understanding of the world, breaking apart the limits we constructed to make sense of the world, to go down the path of futher bifurcations, into what for us seem like chaos. However, it is not the case that less limits is necessarily more correct – it is just two different kinds of knowledges. It is not the case that conceiving of a system that has gone through less bifurcations is less ”true” – it still consists of the same sort of components! I do not think it is necessary for us to a priori take a position on which of model monism or pluralism is the best.

Computation/technology, then, becomes important for us if we are striving towards more global understandings. This seems to me to be very relevant when it comes to our world right now, with our struggles with capitalism, and environmental changes. This highlights the connection between speculative thought and novel technologies. However, this does necessarily imply that I think that technology is liberating, or that it is something good by itself. For example, technology helping us conceive things further into chaos will by definition lead to an alienation from ”the human”. Some considers this a good thing, some less so. I do not think that there is any intrinsic value to be found in technology – however – it is necessary to use as a tool. The only solutions we will find, will be immanent to capitalism and civilization itself. This requires inhuman understandings. It requires us heading into chaos to grasp what is occuring and from it attempt to weave threads of becomings into speculative visions.

I think this makes it clear: having an ideal world, and working for it, is then not actually necessarily a clear path towards making your utopia real – it is just engaging in a process of our world, here and now. It is a tool to transform things right now, not an attempt to construct the ideal. By agitating for communism, you do not necessarily get closer to communism. This is something you could say that Marx recognized, being what he’d call idealist. He never argued that we would get to communism by believing in it, or arguing for it – it was to be the result of a tendencies/forces inherent to capitalism, intensifying until they would reach a point at which they transformed into the next step of the process of civilization – which he argued was to be communism.

Of course, we are some of the tools for that process to play out – us proposing communism is one way the intensification of these forces could be said to express themselves – but it is not what we propose that we necessarily trend towards. Considering the complexity of the forces active – it does not seem necessary to me that it would be specifically communism we would get by intensifying our agitation. What the result of that agitation will be, depends on which particular system you find yourself in: that is, what context. For there to actually be a correspondance between what we work for, and what we are actually heading towards, we need chaotic understandings from going past the edges of our ability to make sense of things. What you need is a speculative ethics, engaging with, and expanding, what is thinkable – and in extension, doable.

En reaktion till “Philosophical Applications of Dynamical Systems Theory”